Lyrid Meteor Shower: A Summary

What Is the Lyrid Meteor Shower?

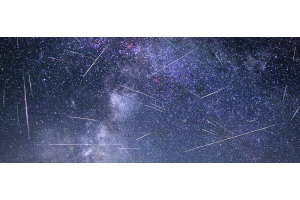

After the Quadrantids in January, the April Lyrid meteor shower (aka, simply the Lyrids) is the next major shower of the year, and typically reaches maximum around April 22nd/23rd. It’s one of two showers that has its radiant within the constellation Lyra, the Lyre. However, the other - the eta Lyrids - is a relatively minor shower and doesn’t reach its maximum until May 10th.

The Lyrids themselves have a zenith hourly rate (ZHR) of 18, which is probably about average for a major shower (not accounting for the Quadrantids, Perseids and Geminids, which all have an exceptional ZHR of 100 or more). This, plus the fact that the meteors themselves are relatively bright (magnitude 2), means that even under less-than-ideal conditions, you should be able to spot a shooting star or two.

There are a couple of things to note about the Lyrids: firstly, they have been known to produce fireballs bright enough to cast shadows for a split second. These fireballs then leave behind trails of smoke that can last for several minutes.

Secondly, roughly every 60 years the shower experiences something of an outburst, with zenith hourly rates in the hundreds. This is due to the dust trail left behind by the shower’s parent body, Comet Thatcher (C/1861 G1). The comet itself orbits the Sun once every 422 years, but every 60 years the planets align in such a way as to gravitationally influence some of the dust, causing a larger dust cloud to form. The Earth then passes through the cloud and observers see a rise in activity.

Image Credit: Yuri Beletsky (Las Campanas Observatory, Carnegie Institution)

The History of the Lyrids

The Lyrids have been observed for over 2,600 years, with the first recorded observation (and the earliest recorded observation of any meteor shower) dating back to 687 BCE. On March 23rd of that year, Chinese astronomers noted that the “stars fell like rain” at midnight.

This event was one of the regular 60 year outbursts mentioned above that have occurred throughout history. More recently, another outburst occurred in 1803, when an estimated 700 meteors an hour were seen between 1AM and 3AM from Richmond, Virginia, causing alarm among residents. A journalist noted the meteors “seemed to fall from every point in the heavens” and compared the display to “a shower of sky rockets.”

Other outbursts occurred in 1922 and 1982, but neither were as prolific as the 1803 outburst, with roughly 90 meteors an hour being recorded on each occasion. There is no record of an outburst in 1862; this is a curious lack of activity, given that Comet Thatcher had reached perihelion in June the previous year. The next outburst won’t occur until around 2042.

Lastly, the Australian Aboriginal Boorong tribe associate the shower with the Malleefowl bird. The shower’s maximum coincides with the bird’s nest-building season; to the Boorong tribe, the star Vega represents the bird, while the meteors themselves represent the scratchings of the bird as it builds its nest.

How Can I See the Lyrid Meteor Shower?

With a few exceptions, meteor showers are best observed in the early morning hours after midnight, when the constellation from which they appear is rising in the eastern hemisphere of the sky.

The radiant of the Lyrids is eight degrees to the southwest of the star Vega and rises around 10:30PM on the evening of the 22nd. You can, of course, step outside once the sky is truly dark (usually about 90 minutes after sunset) and try your luck, but it’s usually best to wait until the early hours of the 23rd, when the radiant is sufficiently high in the sky. For the Lyrids, that means waiting until around 12:30AM, when the radiant is at an altitude of approximately 30 degrees and has cleared the thicker layers of atmosphere that cling to the horizon.

Again, as with all meteor showers, don’t look directly towards the radiant, as this is the area of sky from which the meteors will appear to originate from, not the area from where they will first appear. In other words, you’re more likely to see a Lyrid in another part of the sky, but if you were to trace its path back, it would seem to originate from the radiant.

For the best chance of seeing a meteor, look roughly 45 degrees away from the radiant, as this is the area where they are most likely to appear. In the case of the Lyrids, this means looking towards the north, east or overhead.

A 10 Year Forecast

The table below shows the Moon phase and planets that may be visible above the horizon at 1AM on April 23rd of each year. It should be noted that (again, as with all meteor showers) the date of the maximum can vary a little from year to year and the exact timing isn’t typically known until the International Meteor Organization releases its annual report.

With that in mind, although the Lyrids are typically at their best on the evening of the 22nd and in the early hours of the 23rd, they can occasionally peak on the evening of the 21st and in the early hours of the 22nd. For example, the information for 2025 is for April 22nd, as the shower is predicted to reach its maximum a day earlier that year.

In terms of the rating, if the Moon is below the horizon at that time then its light won’t drown out the fainter meteors, and the rating is five stars. However, if the Moon is above the horizon, then the rating is based upon the phase, altitude and distance of the Moon from the radiant at that time.

Lastly, if the Moon is in the western hemisphere and more than half full, it might be best to wait for the Moon to set before stepping outside. If the Moon is waning and half full or a little less, then it’s best not to wait to observe the shower, as the Moon will only rise higher as the night progresses, potentially causing more interference as its altitude increases.

Learn More

Interested in diving deeper into the world of astronomy? Check out our Astronomy Hub for a wealth of articles, guides, local resources for planetariums and observatories near you, and more to enhance your stargazing experience.