If you’re like most people, you probably got into astronomy for one of the following three reasons: maybe it was the beautiful images you’ve seen online or on TV, or maybe you saw Saturn for the first time through a telescope. Or maybe someone gave you a telescope (although that probably happened after one of the first two reasons!)

Whatever the reason, you’re excited to explore the universe and can’t wait to see these amazing sights for yourself. But what’s the reality of the situation? Can you hope to see anything resembling the images you’ve seen? What factors will play a role in determining what you’ll see?

Light Pollution: Ruining the Night Sky Since 1879

The biggest factor that will likely impact your view of the night sky is light pollution. Light pollution is what happens when the light from a nearby building, town or city brightens the sky to such an extent that all but the brightest stars disappear.

Since the invention of the light bulb in the late 19th century, light pollution has grown in scale, and is now so bad that roughly 80% of Americans can no longer see the Milky Way. And it’s not much better for astronomers overseas either, with approximately 60% of Europeans and nearly a third of humanity as a whole missing out.

As for those beautiful images of the Milky Way you’ve seen, they’re not fake, but they’ve probably been taken from a dark sky location, such as the Joshua Tree National Park in California, or the Grand Canyon in Arizona. (For more information on these locations, check out our guides: The Ultimate Guide to Dark Sky Parks and The Top 10 Dark Sky Parks Around the World.) Unless you live in a dark sky location, you won’t see anything close to resembling those images, and anyone living under light polluted skies will most likely only see the brightest stars. This, in turn, also makes it difficult to identify the constellations.

Unfortunately, light pollution doesn’t just affect the stars or the Milky Way; it also diminishes the number of Deep Sky Objects (DSOs) you can see. A DSO is a star cluster, nebula or galaxy. If you live under dark skies, you’ll be able to see more DSOs, and in greater detail, so it’s worth trying to find the darkest (but safest) location possible to get the best views. (You may want to consider joining a local club or society, as they’ll often have a dark location they can safely observe from.) While light pollution plays a major role in determining what you can see, there are primarily four other factors that will influence the outcome.

How the Weather Affects Your View

The first factor is probably the most obvious, as you won’t be seeing anything if the skies are cloudy! However, it goes a little deeper than that, as there are two aspects of the weather that will impact what you can see, and how well you can see it: transparency and seeing.

It’s best explained using an analogy. Imagine there’s a coin at the bottom of the deep end of a swimming pool. The coin is the object you’re trying to observe, while the water is the Earth’s atmosphere.

If the water is dirty and cloudy, you may not be able to see the coin at all. When it comes to our atmosphere, there may be pollutants (eg, clouds, water droplets or smoke) in the air that make the object difficult to see. In that case, we say the transparency is poor. For example, high humidity can often cause poor transparency, whereas dry conditions will result in clearer skies.

Returning to the swimming pool, if someone jumps in, it will disturb the water and cause it to become turbulent. Under those conditions, you may still be able to see the coin, but it will be difficult (or impossible) to see any detail as the view will be constantly moving.

It’s a similar situation in the night sky. If the air is turbulent, your view of the object will waver as the air passes between you and your target. The term seeing refers to how clearly you can see the object, and it’s directly related to the steadiness of the air. (It’s most obvious when you look at the Moon at high magnification through a telescope.)

It’s rare for you to have both excellent transparency and seeing, but you can still observe some objects if the transparency isn’t what you hoped for. For example, bright objects, such as the Moon and planets, are bright enough to shine through less-than-transparent skies, but you’ll want good seeing conditions to pick out the details.

If the seeing isn’t great, you may still be able to identify the object, but you may have to spend more time at the eyepiece to catch any details. The trick here is to wait for moments of calm, when the air is still, and it’s during those moments that you’ll see more of the object you’re observing.

That said, large, bright star clusters - where the stars are easily seen - can often fare well under below-average seeing conditions, but you may need good transparency to see the fainter stars. The Pleiades star cluster is one example. (Want to know the sky conditions for your location tonight? Check out Astrospheric, a free weather site designed specifically for astronomy.)

What Other Factors Affect Your View of the Night Sky?

The Moon

If you’re new to astronomy, it might seem strange to consider the Moon as an object to be avoided, especially given that it’s probably the first thing you’ll look at with a new telescope. However, the Moon is, essentially, natural light pollution.

It’s a wonderful object to observe in its own right, but when it’s between first and last quarter (and especially around full Moon) it brightens the sky and makes it difficult to see the fainter stars and objects. Try it for yourself; compare your view of the night sky when the Moon isn’t visible with the view during a full Moon, and you’ll see a noticeable difference!

Your Eyesight

The third factor - your own eyes - is, to some extent, a little outside of your control. Not everyone has perfect vision, and the quality of your eyesight will depend upon your age and other factors, such as genetics. As a general rule, younger observers may find it easier to identify and resolve details in fainter objects, but more mature observers may have an advantage - experience!

Dark adaptation is another critical factor related to your eyesight that you’ll need to take into account. Step outside on almost any clear night and you’ll need to allow time for your eyes to adjust to the dark. At minimum, it will probably take at least 30 minutes for this to happen, but you’ll see more stars, plus fainter objects and details.

(Avoid looking at the Moon during this time, and never use a cell phone or regular flashlight, as the light will ruin your eyes’ dark adaption. At the very least, use a lunar filter and a red flashlight, as these will protect your night vision and save you from having to start again.)

Your Equipment

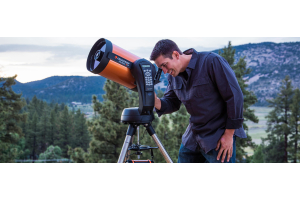

The final factor that plays an important role is the equipment you’re using. It’s not simply a case of seeing more with a telescope than with your own eyes; it also has to do with the quality of the equipment.

For example, the inexpensive telescope at the department store might not be good for anything much, as it will likely have poor quality optics. It’s better to buy a telescope produced by a reputable manufacturer, such as Celestron, Apertura or Sky-Watcher. You can rest assured you’ll get an outstanding telescope, and it won’t necessarily cost you the earth either!

Beyond that, larger telescopes will allow you to see fainter objects and more detail. The reason for this is because they’re capable of gathering more light. Therefore, as a general rule, the larger the telescope, the better your view will be.

What Can You Realistically Expect to See?

Now you have a better idea of what can affect your view, what can you realistically expect to see? We’ll take a look at some common targets and compare the photographs with the view with just your eyes or a telescope, but first, let’s talk about color.

This is possibly the biggest disappointment for beginners, as the photographs online and in books will be full of vibrant colors, whereas the view through a telescope will mostly be gray. This is because the technology used to capture those images is much more sensitive to light than your own eyes. You’ll also find that the images are the result of long exposures, often for several hours, and have been processed and enhanced for maximum effect.

In short, this technology is capable of producing results your eyes simply can’t hope to match. However, as with everything in astronomy, a larger, good quality telescope will produce the best views.

The Stars & the Milky Way

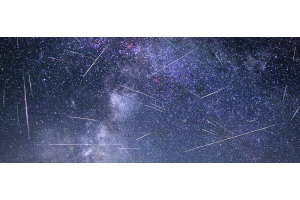

In Photographs: A sky full of stars, with a blue-white Milky Way arching up from the horizon.

The Naked Eye: From the suburbs, you’ll most likely only see the brightest stars, and the Milky Way won’t be visible. From darker locations, you’ll see more stars, and the Milky Way may appear as faint, gray misty patches overhead. A truly dark location, far away from the lights of any towns or cities, will show a multitude of stars, with the Milky Way as a gray, misty river across the sky. Under the very best conditions, and with your eyes fully adapted to the dark, you may even see your own shadow cast by the Milky Way.

Through a Telescope: Generally speaking, you’ll see a lot more stars when you look at the Milky Way through a telescope, compared to a random area of the night sky. However, as with the naked eye, you’ll see a lot more stars if you’re under dark skies, compared to any location that’s suffering from light pollution. Under the best conditions, the view can be filled with countless stars, every one of which lies within the Milky Way itself.

The Moon

In Photographs: Sharp, detailed views of the Moon’s surface, often showing spectacular shadows in craters and cast by mountains.

The Naked Eye: While it’s easy enough to see the phases of the Moon and the dark patches (or, ‘seas’), you won’t see any shadows. You may be able to spot the craters Tycho and Copernicus around full Moon, but the Moon itself can be dazzling.

Through a Telescope: This is one situation where the view through a telescope can potentially match the images, but it will depend on the seeing and the quality of your equipment. Good quality equipment, capable of providing high magnification views, combined with steady seeing, can produce some truly breathtaking sights.

The Planets

In Photographs: Large, colorful views of the planets, which often includes atmospheric or surface details, the largest moons, the Great Red Spot on Jupiter and the rings of Saturn.

The Naked Eye: While five of the planets (Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn) are visible to the naked eye, they’ll only appear as bright, star-like points of light.

Through a Telescope: In the vast majority of cases, the planets will only show a very small disc, with little detail being visible. For example, even through the best and largest telescopes, Uranus and Neptune will only appear as tiny discs. However, almost any telescope will show dark bands across Jupiter and its four largest moons. Saturn will show its rings and three or four of its moons, and when at its best, Mars will show some surface markings. A larger telescope is required to see Jupiter’s Great Red Spot, and only the largest amateur telescopes and good seeing will produce the views you might otherwise see online.

Comets

In Photographs: The appearance of a comet in a photograph can vary, depending on the comet itself and when the photo was taken. Older photographs often show a comet with a glowing white head, and a long, misty blue-white tail that can stretch across the sky. More recent images will show the comet with a white or green head, with a long tail against a backdrop of stars.

The Naked Eye: Comets are rarely naked eye objects, but when they are, they usually appear as misty stars with a faint tail that points away from the Sun.

Through a Telescope: Not unlike the view with the naked eye, the core of the comet will often appear starlike, but surrounded by a gray or greenish mist, with a misty tail pointing away from the Sun. Comets can vary greatly, and equipment and local conditions will play a large role in what you’ll see.

Multiple Stars

In Photographs: Not usually imaged, but will often look like a pair of large, bright stars with four “spikes.” Albireo, for example, will appear as a large, gold star with a smaller, sapphire-blue star beside it.

The Naked Eye: Very few stars appear as double to the naked eye. The classic example is Mizar & Alcor, in the Big Dipper. Double and multiple stars will only appear as two stars very close together.

Through a Telescope: The view through a telescope isn’t too far off a photograph, except that the stars will appear as points of light, minus the spikes. Colors might also be muted, while the stars themselves often appear very close together and may be difficult to split.

Image Credit: Sebastien Lebrigand

Open Star Clusters

In Photographs: Beautiful views of hundreds of stars clustered close to one another, often showing a golden star or two, and sometimes with some associated nebulosity.

The Naked Eye: Very few open star clusters are visible to the naked eye, with even fewer showing themselves for what they are. The Pleiades and Hyades are two examples that can be seen from the suburbs. The few that are visible (eg, the Double Cluster or the Beehive) are more likely to appear as tiny, misty patches, and you’ll need to be under dark skies to see them.

Through a Telescope: Views can be impressive, especially under dark, transparent skies. The number of stars you’ll see will really depend upon your equipment and local conditions, and some stars will definitely show color. One area in which a telescope usually beats a photograph is in the shape of the target. Photos will sometimes show too many stars, and the shape of the cluster will be lost. However, a telescope will allow its shape to remain apparent. NGC 457, the Owl Cluster, is a good example.

Globular Star Clusters

In Photographs: Globular clusters are spherical, and images will often be stunning and show a circular grouping of thousands of stars. Most will be white, or blue-white, with some being yellowish or even golden.

The Naked Eye: All but a few are invisible to the naked eye, and of those that are, they require dark skies to see them. They appear starlike, but very slightly misty. For example, one - Omega Centauri - was thought to be a star before the invention of the telescope revealed its true nature.

Through a Telescope: Depending on your equipment, most will appear as small, hazy patches. Some will appear to have a starlike core, and some may appear slightly elliptical or elongated. With larger clusters (eg, Messier 13) you’ll see the individual stars of the cluster, sometimes all the way to the core, along with streams and chains of stars originating outward from the core of the cluster itself.

Nebulae

In Photographs: Nebulae are stunning objects to photograph and will typically show deep red, green or blue colors, along with exquisite and imaginative textures and a sprinkling of bright stars.

The Naked Eye: Realistically, there is only one nebula easily visible to the naked eye from the northern hemisphere - M42, the Great Orion Nebula. It appears below the three stars of Orion’s belt as a tiny, misty patch with a central star.

Through a Telescope: Results will vary, depending on the nebula. Large, bright nebulae - such as M42, or M8 (the Lagoon Nebula) - will show as gray, misty clouds but may show hints of green or red. Stars associated with the nebula will be visible, along with some texture. A large telescope is always better, and unless you’re under very dark skies, you’ll also need to use a filter.

Planetary Nebulae

In Photographs: The vast majority of planetary nebulae are small and faint, and consequently, they don’t tend to be targeted much. However, common targets (such as the Ring Nebula or the Clown Face Nebula) will show as small, circular discs or rings, with a blue or blue-green tint.

The Naked Eye: With the possible exception of NGC 7293, the Helix Nebula, there are no planetary nebulae visible to the naked eye.

Through a Telescope: Most will appear as tiny, gray discs, about the size of Jupiter or Saturn (hence the planetary nebula moniker). Some will look like a smoke ring (the Ring Nebula being the classic example), some will show a hint of blue-green color, and some will show the central star from which the nebula originated. A lot will depend upon your observing location and equipment.

Galaxies

In Photographs: Like nebulae, galaxies can look stunning in photographs. They’ll often be awash with blue-white colors, filled with stars, and (depending on the galaxy) show a bright core with spiral arms curling outward from the core.

The Naked Eye: Only a couple of galaxies are visible to the naked eye, with M31, the Andromeda Galaxy, being the most accessible. It appears as a tiny, misty patch, much like a nebula, under dark skies.

Through a Telescope: Of all the things you can see in the night sky, galaxies are probably the targets that have the biggest difference between photographs and reality. With a few exceptions, they only appear as faint, gray smudges, barely discernible against the background sky. Some will show a little detail, but you’ll need a larger telescope, dark skies and - like nebulae - a filter to make the most of the experience.

Learn More

Interested in learning more about nebulae, galaxies, planets, and more? Not sure where to begin? Check out our Astronomy Hub!