There’s nothing in astronomy - and rarely anything in nature itself - that can rival the wonder and spectacle of a total solar eclipse. It’s an event that’s instilled both awe and fear for thousands of years, and it’s a sight that, once seen, can never be forgotten. Those who experience it will often seek it again, anxious to relive the fleeting moments of totality that bring darkness to a previously sunlit world.

But what is a solar eclipse? What are the different types of solar eclipse? And what can you expect if you’re lucky enough to experience one?

What is a Solar Eclipse?

Put simply, a solar eclipse occurs when the Moon passes between the Earth and the Sun, which, in turn, causes the Sun to be obscured by the Moon. We live at a fortunate time in the Earth’s history; the Moon is roughly 400 times smaller than the Sun but is also 400 times closer, and as a result, the Moon appears the same size as the Sun in the sky.

(In case you’re curious, both the Sun and the Moon appear approximately half a degree in size. For reference, there are 90 degrees from the horizon to the zenith, the point directly above your head.)

Since the Moon has to pass directly between the Earth and the Sun, a solar eclipse can only occur at the new Moon. A new Moon occurs roughly once a month - so why don’t we see an eclipse with every new Moon?

The reason is because the Moon’s orbit is tilted slightly, so there are months when the Sun, Moon, and Earth don’t perfectly align. Since the Moon’s orbit is also elliptical, there are times when it’s a little too far from the Earth, and it appears a little smaller in the sky. As a result, it doesn’t cover the Sun completely. In order for a total solar eclipse to take place, the Sun, Moon, and Earth must be in alignment, and the Moon must be close enough (and therefore appear large enough) to entirely cover the Sun.

Not everyone on Earth will be lucky enough to experience an eclipse when it occurs. For starters, of course, the Sun is below the horizon for anyone on the night side of the Earth.

But not everyone on the daylight side will see an eclipse either. As the Moon moves between the Earth and the Sun, it casts a shadow that also moves across the surface of the Earth. This is known as the path of totality.

The Sun, Moon, and Earth are only aligned within the shadow, and only those observers within the path of totality will see a total solar eclipse. For anyone to the north or south, the alignment isn’t complete, and they might only see a partial eclipse instead.

At most, when the Moon is closest to the Earth, the path can be 267 km (166 miles) wide. When the Moon is closer to the Earth, its shadow is larger, and consequently, the path of totality is wider. In this situation, totality also lasts longer, as the Moon appears slightly larger in our sky and therefore takes longer to pass in front of the Sun.

The longest eclipses can have a period of totality lasting seven and a half minutes, whereas the shortest eclipses can last mere seconds. On average, you can expect to experience totality for between two and four minutes, depending upon the circumstances of the eclipse itself.

What Are the Different Types of Solar Eclipse?

On average, a total solar eclipse will take place about once every 18 months to two years, but there are other, albeit less spectacular, eclipses that occur more frequently. For example, a partial solar eclipse occurs when the Moon only covers a fraction of the Sun’s disc. This happens when the Sun, Moon, and Earth aren’t in precise alignment or when a total solar eclipse is observed from outside the path of totality.

An annular eclipse occurs when the Moon is a little further away and appears smaller than the Sun in the sky. In that situation, it won’t completely cover the Sun’s disc, and observers see a ring of light instead. Annular eclipses typically occur every 12 to 18 months, but occasionally the gap will be longer or shorter.

Lastly, a hybrid eclipse is a combination of a total and annular eclipse. Observers at the start or end of the path of totality will see an annular eclipse, while those near the middle will see a total solar eclipse. This happens when the Moon is slightly further away for observers at the start or end of the path of totality, and the Moon, therefore, appears a little smaller.

What Happens During an Eclipse?

If you’re lucky enough to experience a total solar eclipse, you’ll notice several distinct phases. The partial phase is first. This is when the Moon slowly moves across the face of the Sun and partially obscures it. As it moves, more and more of the Sun disappears from view.

First contact occurs when the edge of the Moon first touches the edge of the Sun, and the partial phase begins. The time from first contact to the start of totality (known as second contact) is typically about an hour and a quarter.

For most of that time, you may not notice any change at all. It’s not until most of the Sun’s disc has been covered that you’ll notice that your surroundings are a little darker. You might also notice crescent-shaped shadows beneath trees. This happens when the partially covered Sun shines through the translucent leaves; the leaves act as a pinhole camera and project an image of the Sun onto the ground.

As the light fades, you might also notice the colors around you losing their contrast - the effect is similar to what you see when wearing sunglasses on a normal, sunny day.

The Moments of Totality

With only a minute or less to go, there are a number of fleeting events you might experience before totality. For example, you might notice a phenomenon known as shadow bands. These thin, wavy alternating lines of light and dark can be seen moving across the ground and are caused by the Earth’s atmosphere refracting the last of the Sun’s light.

You might also see the shadow of the Moon rapidly approaching your location. This can happen in several ways. Firstly, as the shadow races toward you, you might notice the shadow moving across the sky above your head, like a blanket being thrown over you.

The second way you might notice this is if you’re standing at the summit of a large hill or mountain. Anyone able to see the surrounding landscape from a reasonable altitude could also see the large, dark shadow of the Moon rapidly rushing across the Earth’s surface until they’re engulfed in darkness.

With only about fifteen or twenty seconds remaining, you’ll start to see a white, ghostly fire surrounding the blackened disc of the Sun - the corona. This is the outermost portion of the Sun’s atmosphere, and it extends millions of kilometers out into space.

Next, you’ll see an effect known as the “diamond ring.” At this point, almost the entire surface of the Sun is covered by the Moon, but a tiny, brilliant spark of sunlight will still be visible before it’s snuffed out by the lunar disc.

This spark looks like a diamond, with the Sun’s corona forming the ring itself. Mere seconds before totality the diamond disappears to be replaced with Baily’s beads. These occur when tiny beads of sunlight shine through the gaps in the Moon’s uneven, rugged landscape.

At last, we come to totality and second contact. The sky has darkened. The temperature, lacking the warmth of the Sun, has dropped (often by around ten degrees), and a slight breeze may be blowing. Birds and animals are silent, fooled into thinking that night has fallen.

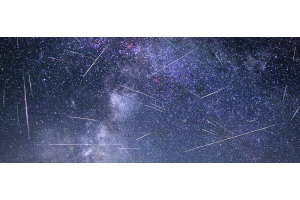

In the sky above, the scene echoes the twilight before sunrise or following sunset. The brightest stars and planets now shine. Mercury and Venus, closest to the Sun, are frequently visible, but you may also see the other naked eye planets: Mars, Jupiter and Saturn.

Now’s the time to savor the moment, as minutes later, it will all be over. Third contact brings the end of totality, and the events reverse as the eclipse unravels. Bailey’s beads disappear to be replaced with a new diamond ring. The solar corona vanishes as the Moon moves away, and the stars and planets fade as the sky brightens.

Your surroundings brighten too, the Sun’s light strengthening as more of its disc is revealed. The Moon’s shadow has raced past and is hurtling onwards to other observers. It’ll be another hour or so before fourth contact when the Moon has entirely uncovered the Sun’s disc. At that time, the eclipse will be officially over, and the magic will be long gone.

With total solar eclipses ranking among the rarest and most amazing of astronomical events, it’s no exaggeration to describe them as once-in-a-lifetime opportunities. There’s simply nothing on Earth that can compare to it, and it’s little wonder that some will devote so much time, energy, and money to experiencing those precious moments again.

Science may explain the mechanics and predict, with clockwork precision, the dates, times, and locations of each eclipse, but the experience itself is indefinable.

Learn More

Interested in learning more about what's going on in the sky? Not sure where to begin? Check out our Astronomy Hub to learn more!

Click the arrow above to see MLA, APA, and Chicago Manual of Style citations.

MLA:

Bartlett, Richard. "What is a Solar Eclipse?," AstronomyHub, High Point Scientific, 21 May 2024, https://www.highpointscientific.com/astronomy-hub/post/what-to-expect-from-a-solar-eclipse.

APA:

Bartlett, R. (2024, May 21). What is a solar eclipse?. High Point Scientific. https://www.highpointscientific.com/astronomy-hub/post/what-to-expect-from-a-solar-eclipse

Chicago Manual of Style:

Bibliography:

Richard Bartlett. "What is a Solar Eclipse?," AstronomyHub (blog), High Point Scientific, May 21, 2024. https://www.highpointscientific.com/astronomy-hub/post/what-to-expect-from-a-solar-eclipse.

Footnote:

Richard Barlett, "What is a Solar Eclipse?," AstronomyHub, High Point Scientific, May 21, 2024, https://www.highpointscientific.com/astronomy-hub/post/what-to-expect-from-a-solar-eclipse.

This Article was Originally Published on 10/12/2022